Trying to figure out the records that exist at Ukrainian archives is challenging for those who don’t know Ukrainian. Archives in Ukraine don’t have a standard format for how they set up their websites.

Thanks to this Wiki site, the struggle is much easier. The website is in Ukrainian but it is the easiest way to view the lists of fonds (sets of records) at many Ukrainian archives.

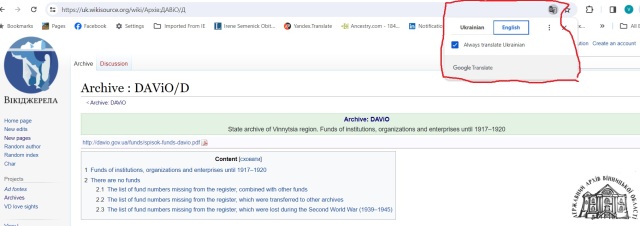

(This Wiki site can be easily viewed in English by downloading Google Translate as an extension to your web browser or use this link to view the site in English. The only disadvantage of using Google Translate is that too many times places and surnames will be translated into common words, not into the letter-by-letter transliteration for English.)

(This Wiki site can be easily viewed in English by downloading Google Translate as an extension to your web browser or use this link to view the site in English. The only disadvantage of using Google Translate is that too many times places and surnames will be translated into common words, not into the letter-by-letter transliteration for English.)

Thankfully, the Wiki site has a search engine to make it even easier to use the resource. A search engine is available for the entire Wiki, in addition to search engines for archives within the Wiki. Keep a window open with Google Translate next to the Wiki site to translate keywords into Ukrainian for the search engines.

The lists of fonds are broken into three groups: record sets before the Soviet period, the period after 1917 and communist party and Komsomol organizations. Not all archives have lists of fonds for the communist party and Komsomol organizations.

Once a fond of interest is found, copy and paste the fond listing in Ukrainian and English into a Word document. Then post in Ukrainian genealogy groups on Facebook to see if any members are familiar with the records from the fonds. For a thorough list of Eastern European-themed genealogy groups, check out the Genealogy on Facebook page.

The simple way to get the site to switch back and forth between Ukrainian and English is to click on the Google Translate app symbol at the end of the address bar and click on Ukrainian or English.

If nothing is found with the above tips, use the find tool in your web browser to locate keyword matches within a particular page. On Windows-based computers, press Ctrl F together and copy and paste keywords in Ukrainian into the search box.

When results are not found, start taking one letter at a time from the end of each keyword. The grammar case of the keywords translated on Google Translate could be different from what the grammar case being used on the Wiki page. Up to the last three letters could be within the spelling difference, causing nothing to be found. For example, Kaniv district likely will be translated by Google Translate as Канівський повіт but the listing of a fond on the Wiki site will have it written as Канівського повіту.

Besides the fonds being listed for Ukrainian archives, the Wiki also has a list of fonds for the Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts, a thorough section for Jewish genealogy resources and scans of audit tales (records similar to census records) for Volyn Province and Kyiv Province.

I know it is challenging to use websites in Ukrainian but it is well worth developing a comfort level with these websites. It saves money on genealogy research and the joy of being the one to find the discoveries, not paid researchers, is priceless.

Follow this blog with the top right button to catch the latest posts on the best free resources for Ukrainian and Russian genealogy without knowing the languages.

Related posts:

New unique database indexes lists of almost 300,000 fonds at Russian archives

MyHeritage launches free Wiki site with valuable Eastern European genealogy resources

Top tips for researching Ukrainian and Russian resources on Genealogy Indexer

Expert guide to using Google Translate in Russian and Ukrainian genealogy